This is the range of notes played on any brass instrument when no valves, slides or finger-holes are utilised. It’s terrifically important for ancient and historical brass instruments as it effectively controls what can be played on them.

As any brass player knows, the ‘open’ notes are the still basis of any of the brass and pressing down one or more valves, or pushing a slide out simply creates a different natural harmonic series which contains different notes. The notes of any particular harmonic series are known as harmonics.

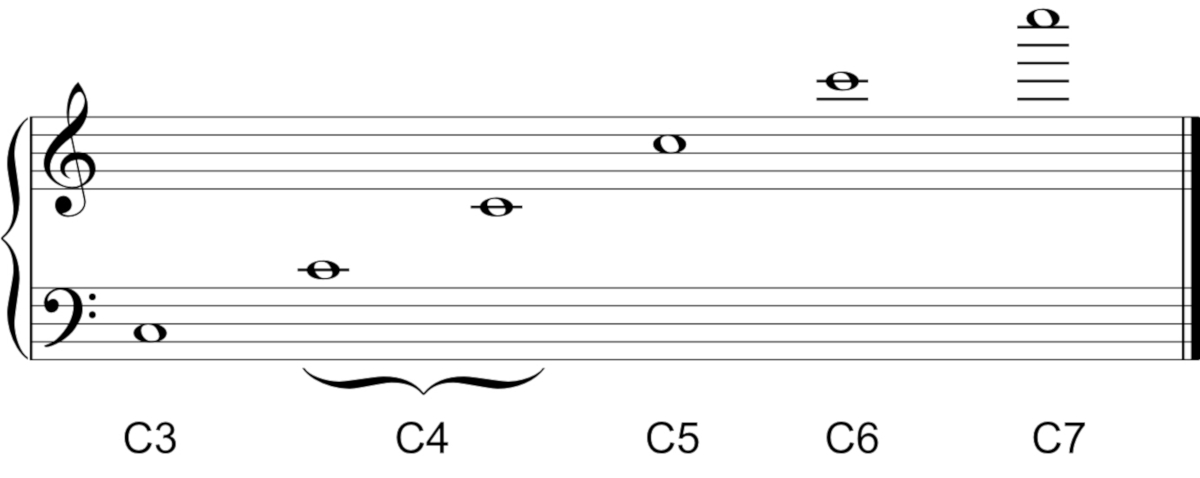

It’s easiest to talk about what ancient instruments played when we use modern notation, that’s the five lines and the signs to tell us whether we are looking at treble, bass, tenor or whatever clef. As each note, such as ‘C’ can appear a number of times, we also need to know which ‘C’ we are talking about. I will use the notation shown on the image in which the C between the treble and bass clefs is called C4. There are numerous other ways of showing this but I find this the clearest.

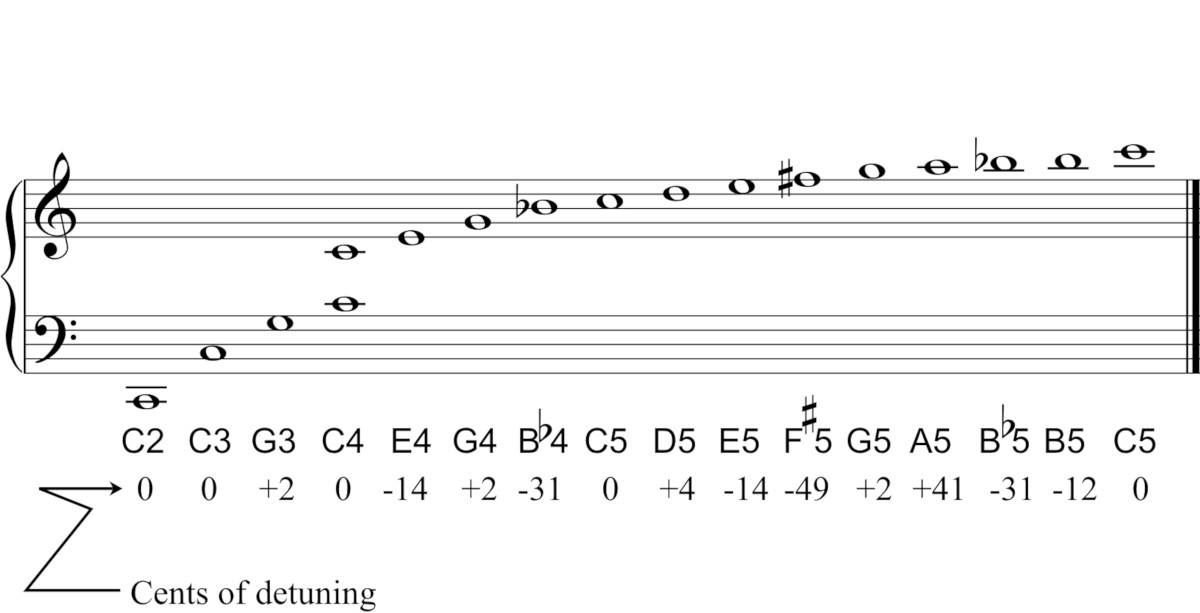

The lowest partial, that’s the deepest note which can be played is referred to as the instrument’s fundamental and, in the image above, that would be C3 in the above diagram or C2 in the diagram below. All the other notes in the series are related to that by their frequency. Today, the basic standard for pitch is set at A = 440 Hz (Hertz or cycles per second) and with that standard the note C2 has a frequency of 65.41 Hz. The next partial (number 2) in the natural harmonic series has a frequency of 2 x 65.41 and number 3 has a frequency of 65.41, etc.

Many instruments are unable to sound their fundamental frequency so the first gap at the bottom of their range, as on the bugle, is from C to G, i.e., a fifth. The other notes in the series are shown in the figure below, along with the proportion of detuning or out-of-tuneness of each note. This latter feature is discussed elsewhere in this blog.