Early Music Archaeology in Ireland and the UK

The modern story of the Irish Horns started in 1726 with a second edition of Gerard Boate’s book. In this, a section written by Sir Thomas Molyneux was added in which he told of a find where feveral Danifh trumpets of brafs were found buried in the earth, fuch as they ufed in war in thofe times, of a peculiar odd make. Most of the writing of this time and some time later referred to these instruments as war trumpets and of their being of Danish (Viking) origin. He provided dimensioned diagrams of these instruments enabling his readers to get a good idea of the size of these instruments.

In a 1784 Ventusta Monumenta Article by an unknown author which made reference to Irish Horns, extensive quotations were given from Greek and Roman authors about the use of their instruments in warfare. This led to the establishment of a view of these instruments as war trumpets, a view which has been difficult to shake off. The confluence of ideas reflected the Greek and Roman axis which dominated thinking about the ancient world in those times.

In an article from 1786, Walker reported that when the owner, Dr Pococke, Bishop of Meath died, his valuable collection of curiofities was fold by auction in London. The trumpets fortunately getting into the poffeffion of the Antiquarian Society of London. This was the first time in this area that concern had been shown for the wellbeing of the objects suggesting that there was an awareness of the need to protect them other than as curiosities. Contrary to this event, much of the literature of the period tells how archaeological objects found in Ireland were valued solely for the metals from which they were constructed.

Walker reported that the music archaeological exploration was continued by a Colonel Vallencey who contacted Dr Burney of London who concurred that [the instruments] might have been a kind of mufical trumpet. Walker added that: One Mr. Rawle, a curious gentleman, of London, poffeffes a trumpet very much refembling the one in queftion, but with two joints, and a perfect mouthpiece. This trumpet was found in England.

A name was given to one of the three horns whose finding was reported in a paper by Ralph Ousley which was given to the Royal Irish Academy in 1788. In this paper, he described it as the Stoic or Stuic, a fort of speaking trumpet, defcribed by Colonel Vallancey in the Collectanea.

Sometime later, in 1850, Smith wrote about the difficulty of understanding how these instruments were played, saying: If the method of filling the german flute was loft, and a perfon was to find one, it would be very difficult to gefs what kind of found it might afford, and the fame may be faid of our trumpets.

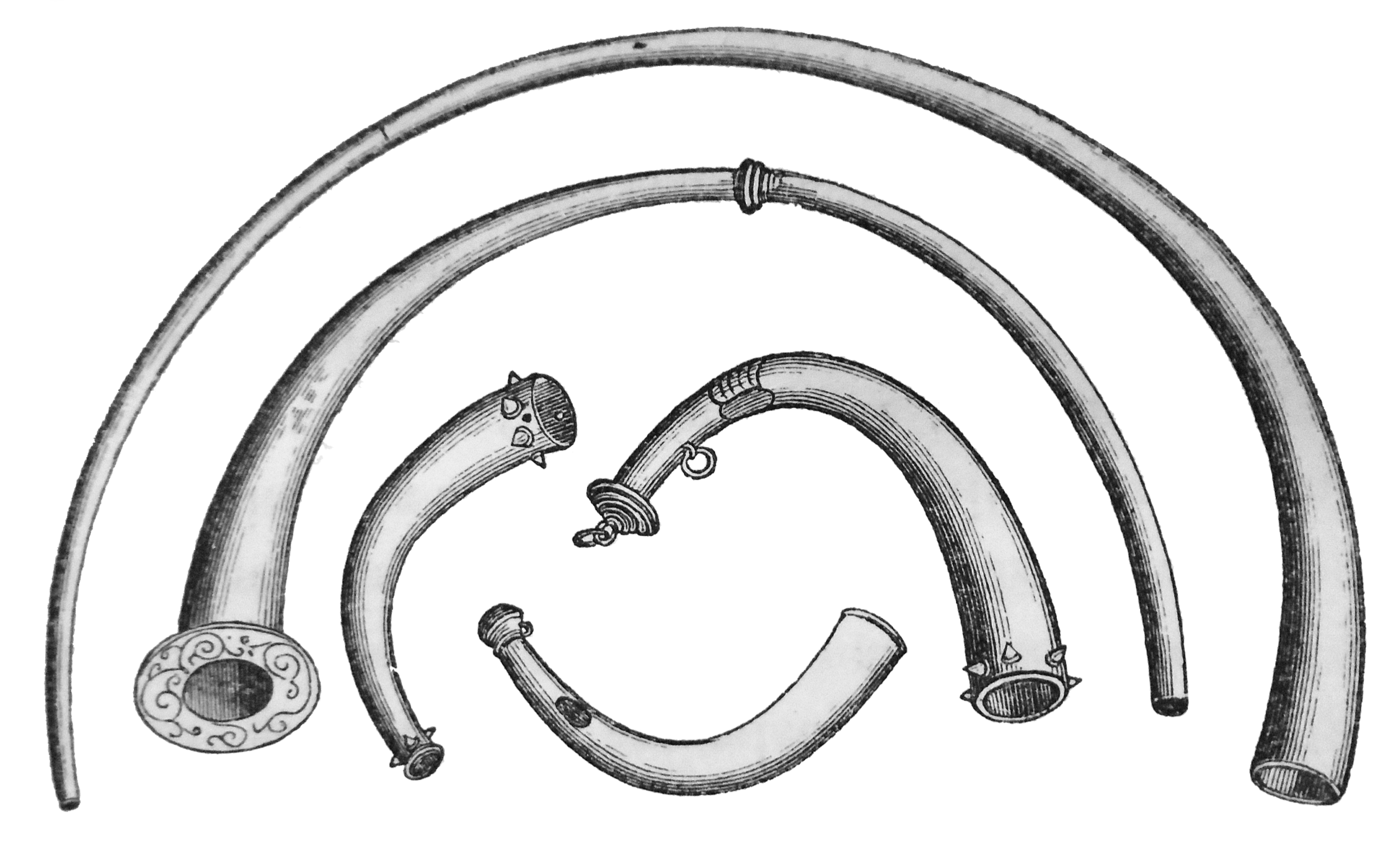

In 1857, William Wilde wrote a Catalogue of Materials in the Museum of the Royal Irish Academy, in this, under the classification Class III, Vegetable Materials and Class V, Metallic Materials, he described all the brass instruments found in Ireland. Although C. J. Thomsen had developed his Three-Period categorization of artefacts in the Royal Museum of Nordic Antiquities in Copenhagen between 1816 and 1825, Wilde, in his chapter, grouped all the instruments from both the late Bronze Age and Iron Age together and, at that time, did not identify them as being from different periods. He wrote: …the commander of a battalion had also his speaking trumpet, as well as his trumpeters beside him, when he fell in battle. That a curved trumpet, attached to each end of a straight tube, four feet long, could not be of any use known or conjectured in the present day, is manifest.

In 1945, MacWhite published an exhaustive study of the horns, creating a comprehensive catalogue of these with very-liberal descriptions of each instrument.

Most recently they have been studied by John Coles who outlines the previous classifications and dating by these authors, and provides his own comprehensive catalogue of all instruments known to that date. This is the numbering system I have adopted for my cataloguing efforts.

In addition, in his 1963 paper, John Coles proposed a new typology which related the design of the instruments to their geographical spread. His observations, by embedding the instruments within specific cultures, led to a better understanding of the relationships between the different cultural groups on the island. In addition, because of the very-generous access to the instruments which was granted to researchers of the time, he was able to blow all the instruments and record the tonality of these.

John Coles’ analysis demonstrated that the first partials of the instruments examined all fell in a very narrow range around what is today seen as the C between the treble and bass clefs or C4. However, the Irish Horns are scattered amongst a number of museums in England and Ireland and it may be that, because all museums were not as generous with the access to instruments in their collections as the Irish museums, the range of instrument tested was not fully representative.

Between 1975 and the early 198os, I worked on these instruments, concentrating on their manufacturing technology and performance capabilities. I shared John Coles’ experience of wonderfully-free access to the instruments in both Dublin and Belfast and from my extensive investigations, was able to demonstrate that workshops in Ireland developed manufacturing technologies which were many centuries ahead of those in the rest of Europe and ones which only saw adoption by the Romans during their Imperial era. Such workshops were very innovative and the manufacturing technologies in use were likely developed in a number of different locations, some being shared and others being seen in only a single occurrence.

In the 45 years or so since this phenomenon was reported by me, it has never been cited demonstrating clearly how the culture of the maker is given scant rcognition among those publishing in this field. It may also be the case that the view of a manufacturing technology existing in Bronze-Age Ireland which was superior to that employed by the Romans is not welcome in the Classical world.

Blowing the Horns

During my period studying the Irish Horns, I created modern analogues of these and was able to demonstrate that, by blowing them utilising circular breathing, they were capable of being played as variable tone colour instruments. I presented these findings at a conference in Dublin in 1978 when the chairman Joseph Raftery asked for an opinion on this view from one of Ireland’s eminent archaeologists. His response was that the idea was fecking nonsense. Needless to say, these instruments and those from the later Iron Age of Ireland, as with the large open-aperture karnyces, are all now played in this way.

Around that time, along with a sculptor friend, John Somerville, I created close modern analogues of the Drumbest pair of Irish Horns, using latex moulds and lost-wax casting. The exercise was prompted by a contact with Simon O’Dwyer who had heard of my experimental work from Dr Raftery in Dublin and got in touch with me. With instruments from our initial casting sessions and many, many more which Simon went on to create himself, Simon explored the potentialities of the horns in amazing ways and became the formost performer on these. By talking in primary schools throughout Ireland, Simon and his wife Maria Cullen expanded the scope of music archaeology enormously throughout Ireland. They also introduced an element which I had never dreamt of when they took the instruments to Australia and shared their western enthusiasm with First Australian performers on the didgeridoo. This outreach aspect of music archaeology is one given scant mention in the literature but is one which grants an existence to the subject which would otherwise not exist.