Like me, you’ve probably read about the ancient ‘War Trumpet’. However, while there’s no doubt that the ancient high brass was used in all sorts of military contexts, it is also clear that they also filled many other roles in ancient societies, those up to the end of the Roman Empire.

In spite of their widespread use in civilian, ritual and religious practices, the term ‘War Trumpet’ is still used to characterise the brass in general. Whether this is because of lack of knowledge of the evidence on the part of the author or simply insufficient attention to terminology, it is unfortunate in the extreme as it misrepresents a time when the brass was used extensively in anything but a simple way. West, for instance, in his book on Greek music comments: It is by courtesy only that we give attention to this instrument [the salpinx or Greek ’trumpet’] as it was not used for musical purposes but only for giving signals1. My personal feeling is that we do not need to be courteous, just respectful.

While the situation regarding the brass is somewhat similar throughout the ancient world, this short article looks at a period of around 400 years, the final few centuries of the Roman Empire. Even more precisely, it focusses on the Graeco-Roman games/agones, events which continued to take place throughout the Greek-speaking areas of the Roman world long after the Romans came to power there.

In a notable development, the Emperor Diocletian instigated, in 62 CE, a Roman version of the Greek games which he named the Capitolia. In doing this, he aimed to establish this as a Roman cultural institution and to make Rome the capital of the games.

The brass had entered the games at some stage in their development, perhaps at the very beginning, perhaps later, whatever the case, it was in 396 BCE, in the context of the Olympic Games, that we hear of the instigation of a competition to choose the salpinktes (salpinx or ’trumpet’ player) who would officiate throughout the games.

In spite of what you might read in the modern literature, we have absolutely no idea of what the criteria were by which this contest was judged.

Xanthoulis uses a Greek inscription describing the herald Archias’ wins to derive some idea of what criteria the judges might have applied to the salpinx contest but, as the text clearly refers to the actions of the herald Archias acting on his own, it cannot enlighten us as to what qualities marked out a good salpinktes in the eyes of the contest’s assessors. Xanthoulis, waxing eloquently on the criteria by which a salpinx contest was judged, offers the opinion:

In order to arbitrate, the judges had to pay attention: to the rhythmical patterns through which the contestants had to control the duration of breathing and the expression of clarity, a prerequisite for the places of worship, [along with] the strength of inhalation to accomplish long phrases and the clarity of that playing [these being] primary factors in the judging of the competition.

While, as a trumpet player myself, I love the sentiment expressed in this paragraph, and can register its appeal to the brass community, I can see absolutely nothing in the literature of the Greek agon to support it2. My perspective is, knowing the Greeks and the attention they paid to the design of their ceremonies and rituals and particularly their games/agon it seems likely that the competition would have favoured those capabilities which enabled the role of Games Salpinktes (’trumpet’ player) to be carried out most effectively. Of course, the player would also need to have to sufficient stamina to last the four or five days of the Games and reputation from earlier appearances at a games which demonstrated their knowledge of procedures might were likely criteria by which they were judged.

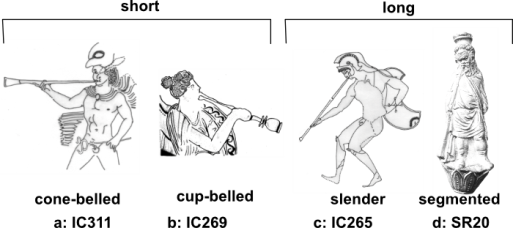

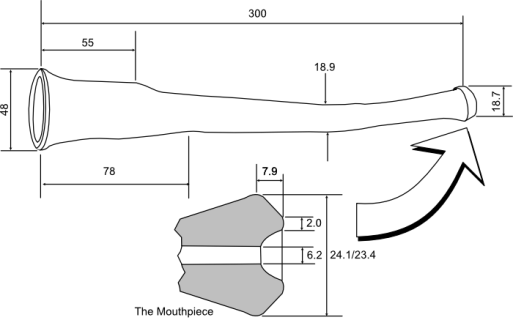

A further criticism of the earlier comment lies in the fact that, while we might reasonably talk of the form and use of ’the salpinx’ at any specific point in time, over the thousand years or so of its existence, its form and use is likely to have changed considerably with the years. Figure 1 shows four varieties of Greek salpinx. For reference data on the four salpinges shown, click as appropriate: IC311: IC269: IC265: SR020:

A different view of judging criteria is offered by the earlier authors, Turrentine and Gardiner,3 who suggest that the contest was for the salpinktes who could play the loudest but it is unlikely that organisers/judges would adopt this one and only criterion to select the winner. Given that the salpinktes (salpinx player) chosen would officiate right throughout the games and would be called upon to perform at many high-profile events, it does seem unlikely that sheer volume would be the only criterion. The organisers would certainly require the salpinktes to follow the laid-down procedures for the running of events and to maintain the dignity of the occasion by performing well while still being able to call the crowd to silence and adding some pomp to the occasion. Considerable knowledge of procedure and protocols would certainly be called for if all these criteria were to be met.

As for applying criteria based upon ’the Greek’s irrefutable sense of beauty’, I feel that functionality may well have taken precedence and the need for a well-run and smoothly-functioning set of events might have called for operational sophistication ahead of non-functional performance criteria.

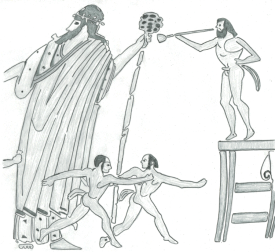

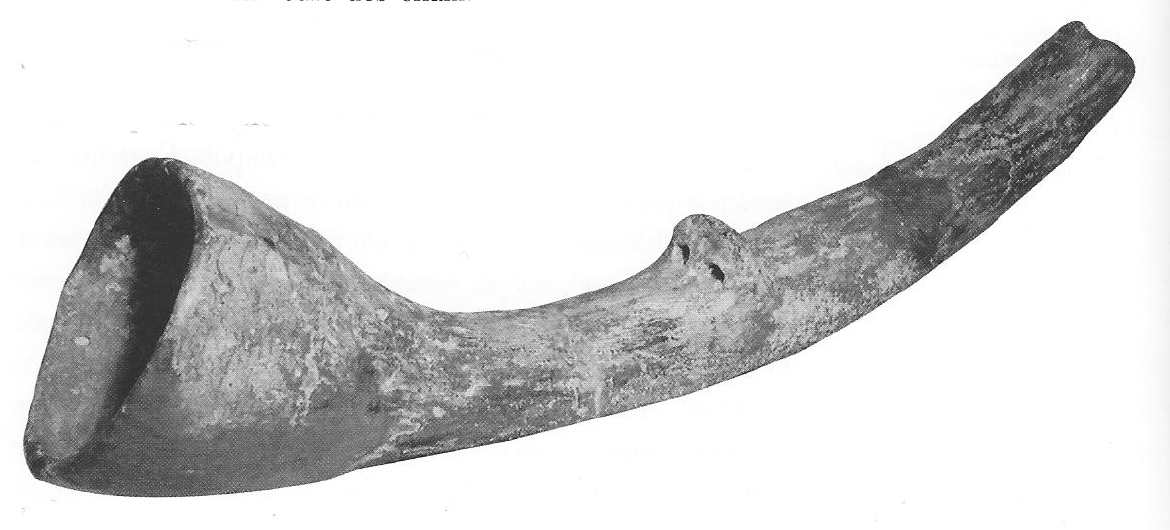

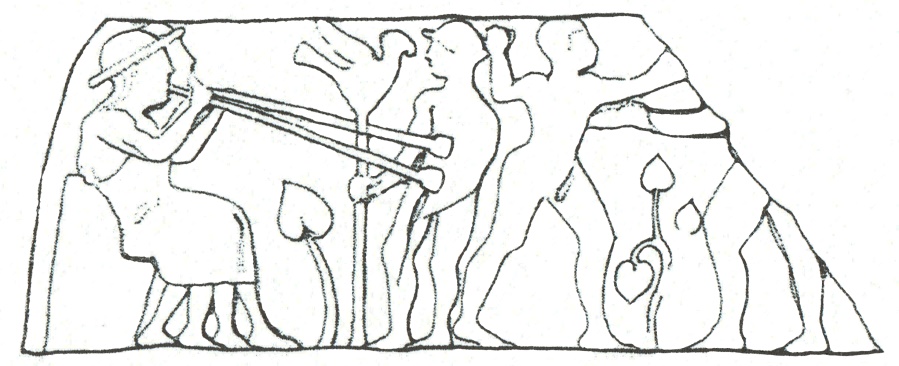

The winner of the contest would be required to call the players to the field of competition, start the race and, in a long race would play to urge the competitors on during the final lap. Following the race, they would blow to announce the winner and mark his attainment as the victor’s crown or wreath was presented. A scene in which the salpinktes starts a running race may have looked something like Figure 2 although this scene is from another context and features mythological figures. We are told in contemporary literature that the officiating salpinktes stood on a dais or altar when blowing to open the Olympic Games4. For reference data click: IC264

Iconography from Greek times generally shows the cup-belled salpinx being used to control proceedings whereas the Graeco-Roman iconography generally shows a more tuba-like5 instrument. I know of only one of the late mosaics which shows an instrument reminiscent of the earlier form, this being shown in Figure 3. On this depiction, from Ostia near Rome, the salpinktes/tubicen is wearing Roman attire and a victor’s crown while holding his left hand up to this to indicate that he is a winner of the salpinx contest. Such winners are predominantly shown alongside the herald and this complementary duo is one seen from much-earlier times in other contexts as well as the games6. As a duo, they drew attention to their presence by a call on the salpinx and then delivered their message by an oration from the herald. The salpinx from Ostia is shown on one of the black/white mosaics which became popular in the villas of the wealthy in the second to the fourth centuries CE. For reference data click: IC665

Unlike in the image in Figure 3, the majority of depictions of such events show a straight, conical instrument with a flared bell and often one which is considerably longer than earlier Greek models. Just what any of these instruments were called is very likely to depend on whether the informant is speaking Latin when it would be tuba or Greek when it would be salpinx.

In spite of the change of the salpinx’s form in later depictions, the players of the instruments are still shown wearing the victor’s crown as was the earlier tradition, indicating that the salpinx/tuba contest still took place and that they had won this.

Much of the evidence for these instruments comes from mosaics, particularly black and white ones. The mosaics in the rich villas of Sicily and North Africa were huge and depicted the very wide range of activities which took place in the games. Figure 4 shows a scene from a mosaic in which a salpinktes blows a long tuba. He is holding his right hand up to a victor’s crown, this indicating that he was the victor in the salpinx/tuba contest. He appears to be blowing to mark the achievement of the successful athlete who is standing to his left. To the left of this athlete stands a defeated competitor who is adopting the characteristic pose of defeat. For reference data click: IC664

While the brass played a key role in the games/agones, one needs to look at the culture which lay behind these activities in order to understand that the instruments were not just there for their functional capabilities. The agonistic ideal was based upon the concept of honourable victory and success which was the result of honest endeavour. Our word ‘agony’ has its root in this ideal and reflects the pain expended in becoming the best at what one does. The reward of the winner could be a simple wreath or, as shown in Figure 4, a crown of roses, often five in number.

The importance of the successful tubicen/salpinktes being adequately rewarded is reflected in the ceremony in which he was presented with his crown. In the traditional games/agon, only one prize was awarded, the one for the winner: there was no gold, silver, bronze in the ancient games. Thus, as it was the role of the winning salpinktes to play at the presentation of a crown/wreath, there could be no-one to play for the winning tubicen/salpinktes. In order to deal with this problem, at some stage, a runner-up began to be recognised in the salpinx competition, this being the only contest in which two winners were acknowledged. It may have been such a practice which led to another major brass development in the games but that’s for another article.

The agonistic meetings included both theatrical and musical events and this raises the question of how the later tuba/salpinx contests were judged, i.e. for their signalling/control attributes or on a ‘musical’ basis. Scaling the instruments from the iconography, yields instruments of around 8-foot C, i.e., ones pitched around the same as those which would have been seen in the Renaissance and Baroque Periods, albeit ones lacking the bends of these later instruments. Figure 5 shows a player blowing his 8-foot C instrument and the performance characteristics of these instruments is discussed below. For reference data click: IC604b

As I reckoned that these instruments must be able to perform in the way commonly associated with Renaissance/Baroque performances, I set out with my colleagues Spike (Neil Melton) and Martin Sims, also from Middlesex University, to make 3D printed copies of the various instruments seen in the iconography. In the first instance, I tested these with a modern 3C trumpet mouthpiece and the 8-foot C instruments performed just as expected and in a most-pleasing way. The party piece for the instrument became the Trumpet Tune and Air which was the most-satisfying to perform.

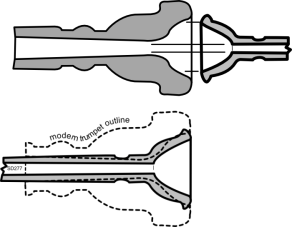

However, in order to justify my assertion that the instrument could be played in this way, I had to go through my next step and search my database of 87 Roman mouthpieces to locate a suitable one for this type of performance. It wasn’t a long search as one popped up which was very like a modern trumpet mouthpiece and the 3D print of this works fine when used with the long tuba. Figure 6 shows a comparison between a Roman mouthpiece and a modern trumpet one. The modern mouthpiece is the thick one in the top left of the picture. For reference data click: SD277

As can be seen in Figure 6, the comparison between the Roman mouthpiece and the modern one reveals that, while these are not identical, they are very similar functionally.

As for the tone colour of the ancient instrument, it does differ from that of the 1000-year later trumpet as the Graeco-Roman instrument is totally conical and has a relatively-large bell. It sounds mellow and speaks readily along its entire compass.

Of course, we have no record of what was played on this instrument and no-one would suggest that the Trumpet Tune and Air drifted across the Mediterranean world a thousand years ago. On the other hand, I would suggest that no-one goes to the trouble of making an 8-foot (2.4 metre) long instrument simply to create the loud grunting noises which are frequently attributed to instruments of this time. I would suggest that the partials in the upper register were used to create a performance based upon the same range as one might have heard on Renaissance or Baroque brass as a number of Roman mouthpieces exist which would be suitable for such a performance. Thus, taking into account the form of the 8-foot C Roman tuba/salpinx and its possible mouthpiece, the later term Renaissance Trumpet is a fitting one as it marks the rebirth of the Graeco-Roman tuba/salpinx albeit in a different wrapping.

The Meaning of the Salpinx/Tuba

During the period when the games was a uniquely Greek festival, the salpinx changed little in form. This was in sharp contrast to the other instrument depicted in these celebrations, the aulos. This double-reed woodwind instrument was almost always played in pairs and was developed organologically by the provision of many different types of keywork. Such developments enabled the aulos to be played in all the modes which were in use at the time. The salpinx on the other hand remained a simple arpeggial instrument7 which could sound only partials from the harmonic series. The question arises, therefore as to why this was so and what pressures prevented the early makers from adding mechanisms to the tuba such as those seen on the aulos. A caveat which has to be added here is that we do not know whether there was any interaction between the makers of the aulos and those who created salpinges. In one text, reference is made to the salpinx maker, relating him to his specific specialisation. Certainly the manufacturing technologies used in making the two instruments was quite different although one instrument and a few texts do hint at links between the manufacturing technologies of the two instruments.

In view of an apparent seemingly-universal tendency to see the brass as a Chamber of Creation/Repose8, I see any possible developmental prohibitions as arising from the embedded meaning of the salpinx, a phenomenon which can be traced back to cultures which predated that of classical Greece, these being seen in earlier Minoan and Mycenean civilisations. In Minoan times, the brass, in the form of the shell trumpet derived its meaning from its possession of a cavity which could be interpreted as a Chamber of Creation/Repose. The cup-belled salpinx, which is the form most frequently seen in the purely-Greek agonistic context, consists of two elements: the cup-shaped bell and the straight tube yard, the cup-shaped bell also carrying with it some element of the earlier chambered interpretation.

That the instrument’s bell possessed some meaning is hinted at in the Greek term for this – kodon. Such a term is used to describe both the bell of the instrument and the sound tool which we would refer to as the bell in English, i.e, a ringing bell. As the ringing bell was granted apotropaic powers by many ancient societies, including the Greeks (i.e., the power to ward off evil spirits), the application of this term to the bell of the salpinx implies that this too possessed similar powers, thus locating it in the same spiritual domain.

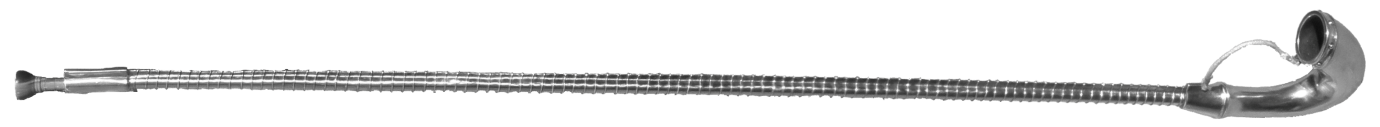

The salpinx shared this characteristic with the Etruscan lituus and the Native European Karnyx both also sharing the overall structure of a chamber into which a tube yard fed. Although ancient Greek depictions of the salpinx show no decoration on the tube yard, the depiction from the Ostia mosaic (Figure 2) shows a cord wrapped helically around this. Such helical decoration is seen on the Pian di Civita and Cortona litui, as well as on Roman coins which show the karnyx. Such a helical decoration itself carried deep meanings in the ancient world – but that’s another story. A modern analogue of the Pian di Civita Lituus is shown in Figure 7. For reference data click: SD306

Thus, to the ancient Greeks, while the salpinx was a useful sound tool, it most likely continued to have some spiritual meaning which extended beyond its sonic capabilities. In which physical element of the salpinx’s makeup such a spiritual meaning might reside is nowhere stated but other ancient parallels might provide a clue, leading to a conclusion that it was probably the bell which held such meaning.

The same comment about where meaning resides is equally true for the Etruscan term lituus9 which was applied to two different Etruscan objects. We know that the lituus held a special position in Etruscan society but have no knowledge of the relationship between the two forms of this object, the silent (ritual) and the sound tool. Both forms appear as pretty-much identical in the iconography and it is not always possible to tell whether the artist is portraying the ritual (silent) version or the sound tool lituus. For reference data click: SR022

Literary references tell us of the role of the silent (ritual) lituus, the major one being in augury. When used in this way, the augur utilised the silent lituus during the process of predicting the future. During the divination process, the augur, standing facing north would use the curved portion of his ritual instrument to link the powers of the underworld and the celestial sphere by rotating this, thus drawing wisdom from both sources or facilitating the flow of wisdom and knowledge between them.

The other use which is identified principally from iconography is in the context of athletic events but the iconography provides no idea of its role in these. This may have been in connection with judging of competitions, the Latin term litigium referring to a law suit. For reference data click: IC578

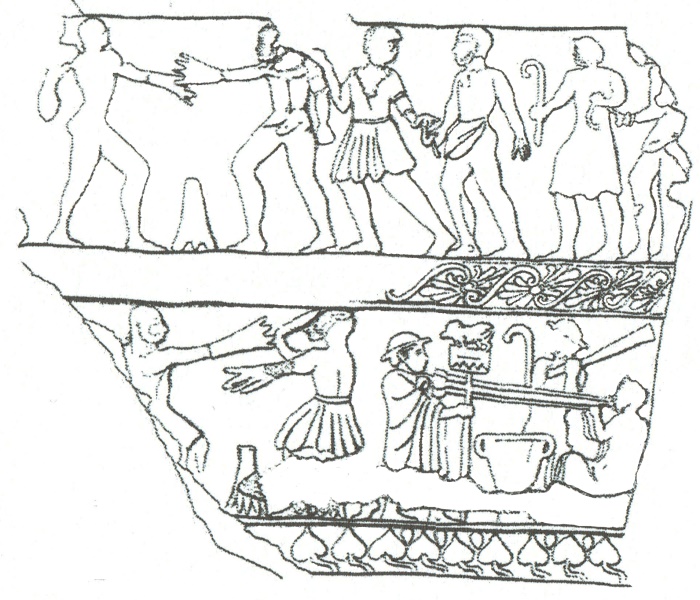

One piece of Etruscan iconography, Figure 9, shows a number of salpinges, possibly three being played at a games during a boxing match. Behind them, another person holds a lituus and a tuba.

This use of the lituus in augury was carried on into Roman times and the Romans reputedly valued the skills of Etruscan augurs.

The importance of the bell is particularly emphasized in the case of the Native European Karnyx where it is given a zoomorphic form, sometimes that of a recognisable animal. One piece of iconography which shows this spanning the spheres is the Gundestrup Cauldron on which the players blow in the lower (human) sphere while their sound emerges in the celestial sphere. Thus, human breath enters the blowing end of the karnyx but it probably is seen as emerging as some mystic medium. In the Gundestrup depiction, the bells of the karnyces are marked out by being created in the form of an animal head10. (Figure 10) For reference data click: IC049

Iconography of the sound-tool lituus shows the instrument in use as a boundary marker, i.e., at liminal junctions. This is seen in Etruscan tomb paintings where the brass, both litui and cornua, are depicted being blown over the gateway connecting the human world to the underworld. In Figure 11, the doorway is the small dark block on the extreme bottom right of the image and the player on the right is blowing a lituus over this. The tuba is never depicted in this way. For reference data click: IC313

Liminal locations for the deposition of instruments at some stage in their lifetime is not an unusual phenomenon for brass instruments in general. In the case of the Brudevaelte bronze lurs, for instance, these were found carefully laid out on the natural ground surface between that and the overlying peat. The Neolithic shell trumpets found in cave deposits around the Mediterranean were carefully laid out among burials, often of young children. The Pian di Civita lituus was found under the stone at the threshold of a ritual building while the Cortona lituus deposit was likely similarly deposited. Such depositions mark the brass out as signifiers of liminality or status change, either in individual societies or for mankind in general

The sound of the horn is referred to in many texts as a marker but, in Norse mythology, for instance, the blowing of the Gjallarhorn is a significant event marking as it does, the beginning of the end of the world and the final confrontation between the forces of good and evil: a liminal time indeed.

The lituus is made up of a downstream animal-horn shaped element and a straight tube yard. This bell section draws on centuries, perhaps millennia, of cultural associations. One prominent association lies in the Biblical reference to Abraham sacrificing a ram on Mount Sinai and the larger right horn of the animal being formed into the shofar which would be sounded in times to come. This is taken to be a reference to the future coming of the Messiah and this is re-iterated in the New Testament when we are told that the trumpet (tuba) shall sound and we shall all be raised incorruptible. Handel took these words and inadvertently scored them in such a way that an instrument from the time of Saint Paul who wrote them in his letter to the Corinthians, would have been able to follow Handel’s score.

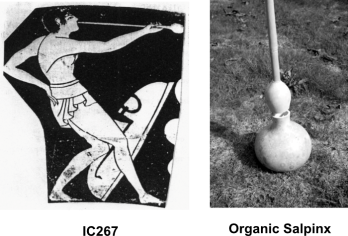

Like the contemporary Etruscan lituus, the salpinx had its distinctive downstream feature but its common termination is in the form of the cup bell, and the earlier bells may have been formed of natural materials11. Figure 12 shows a salpinx which may have been made of organic materials along with a similar instrument which I created from a reed and a gourd.

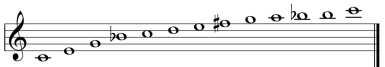

When the organic salpinx was provided with a small mouthpiece something like the size of a cornett(o) acorn mouthpiece, I was able to obtain the notes shown in Figure 13 on this.

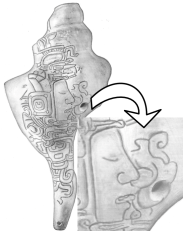

Early Greek culture may be traced back into Minoan times when the sea shell and the sea-shell trumpet were common cultural objects. Around the Mediterranean, shells and shell trumpets were deposited in caves, carefully laid out, particularly along with the bodies of children. In neither of these two cases do we have any references to the meaning of such depositions. However, ethnographic references provide many examples of similarly-used blowing shells, along with indications of the ritual meaning of these and the striking feature of these is the apparent universality of their meaning. Figure 14 show a Mayan, highly-decorated blowing shell or shell trumpet on which Kukulkan, the Mayan God of the Wind (also known as Quetzalcoatl in Aztec mythology) is depicted. This I would characterise as a Chamber of Repose within which the God’s spirit resides, being released to speak by the human who blows the trumpet but sounding only when the fingerhole is opened. The shell trumpet thus possesses two voices, one human and one divine. Having the power to invoke this God is likely to have been reserved for special people in their society. For reference data click: SD459

Some modern religions still see the shell trumpet as a Chamber of Creation/Repose. For instance, some Buddhist communities believe that Buddha hid in a shell trumpet while Vishnu used the shell trumpet and its call in battles with his enemies.

In other reported practices, such as those of the First Australians, their God blew the first humans out of the end of his didgeridoo. Today, the spirit of the God is excited by human breath and the instrument is animised to become the Great Serpent of the Dreamtime. Similarly, in the case of the Western Amazon Tukano, their long wooden trumpets become the Great Anaconda ancestor in a similar animisation.

In Maori culture, the putorino is an instrument which can be played as either a flute or a trumpet and is made in the form of a case moth chrysalis. This form mimics the actual Chamber in which the moth is created, thus gaining an association with the creation process, it being in the natural form where life evolves.

Such meanings are repeated first hand in ethnographic-reports, but this not so in ancient contexts and meanings have to be divined from actual finds or the material associated with instruments, such as iconography, no first-hand information being available. A case in point is the Tutankhamun trumpets.

Both trumpets found in Tutankhamun’s tomb were provided with wooden inserts whose bell portions were painted with an abstract representation of the blue lotus and the bell of the silver trumpet carried the same decoration. This latter instrument was placed directly up against the shrine in the tomb: a very sacred spot. To the Egyptians, the blue lotus was a plant which symbolised rebirth and resurrection so the instruments were providing a chamber into which the symbolic blue lotus painted on the insert was placed. Just what the symbolic meaning of this act was cannot be ascertained but the association of the silver trumpet in particular with birth/rebirth seems strong and this view is re-enforced by the context of its deposition. Notably, it is the bell section on both the silver trumpet and the inserts which are decorated, the tube yards remaining plain. As elsewhere, it appears that it is the bell portion of the instrument which holds the power. (Figure 15) For the reference data click: SD202

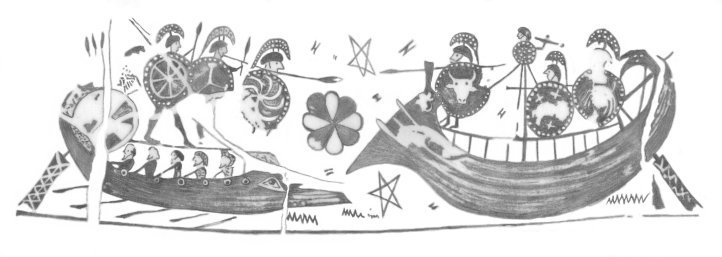

The earliest depiction of a Greek salpinx is seen on vase which was made in Caere (modern Cerveteri, Italy) (Figure 16). It is signed by the artist, Aristonothos who was a Greek immigrant working in Caere around 650 BCE. The scene is allegorical, featuring Odysseus, raising a question about the extent to which one might rely on the depiction of the salpinx. However, assuming that the depiction is reliable, the instrument shown is very long but possesses a termination which could well be interpreted as a chamber of some type. From my perspective, I would tend to see this as an organic instrument, possibly created from a long reed such as Arundo Donax and terminated with a gourd or similar chambered object. For reference data click: IC266

Another possible interpretation of the termination of the Caere salpinktes’ instrument is that it represents and egg. Above, the organic salpinx was discussed which has a termination much in the shape of an egg (Figure 12). Lisa Pieraccini describes a scene in one of the Etruscan tombs at Tarquinia thus:

Tomb 5513, which dates to around 450 BCE, shows Etruscans not only holding eggs in their hands but also flowers, specifically, the lotus12. These handheld objects may share symbolic meaning regarding life and rebirth: the egg could have been a symbol of life and fertility and the lotus (which opens and closes with the rising and setting of the sun) may have connoted life and death. When they are depicted together, the allegory is transparent. The familiar banquet on the back wall depicts a kylikeion (a table with vases for the banquet) on the right. The man in the center holds a lotus flower while to his left a standing woman holds a lotus bud up to a male banqueter on her left, as if for his contemplation. A simila bud can be seen in the Tomb of the Triclinium, painted around 470 BCE, the full details of which exist only in a drawing13. But the lotus appears on many Etruscan works of art, including an engraved bronze mirror (Fig. 6), which may, in fact, also depict eggs in the bowls in front of the banqueters14.19 That these two objects – the egg and the lotus – are often depicted together at funerary banquets emphasizes their social and religious importance.

Regardless of the details of manufacture, the artist is clearly showing a chambered instrument. A much-smaller pottery instrument, found in Cyprus has a chambered termination, this location being in an area from which Greece received cultural inputs, there being strong language connections between Cyprus and the early Greek cultures. The horn dates from several hundred years before the establishment of any sort of Greek identity. It is illustrated in Figure 17. For reference data click: SD279

While the chamber on the end of the Cypriot horn is nowhere as pronounced as on the later salpinges, it is still recognisable as a terminating section with an expanded diameter. Such expanded terminations are seen on other instruments such as the pottery horn from Rouet in France which dates from between 3000-2500 BCE, the local Neolithic Period. (Figure 18) For reference data click: SD350

In none of the three cases cited above, the Caere iconography (Figure 16), the Cyprus pottery horn (Figure 17), or the Rouet pottery horn (Figure 18), can we be sure of the purpose of the expanded chamber section at the bell end of the instruments and all I can say is that I find the interpretation of the bulbous end of these on brass instruments as a powerful chamber rather compelling. Suffice it to say, there is considerably more evidence to support the idea than this article has the space for.

In the case of the Cypriot and Rouet horns, the expanded end termination has an organological impact in that it reduces the end impedance discontinuity, allowing more energy to escape from the windway, thus making the instrument louder. However, the loudness argument does not hold for all salpinx terminations as some are spherical in form with a rather-small exit diameter. As with all modern interpretations of ancient phenomena, it is not always possible to divine what intentionality lay behind the identifiable changes.

Although the Greek and Roman literature reports quite often that the salpinx was invented by the Etruscans, it is rarely depicted in use in Etruscan contexts. One of the few records of its use is in an image which shows two salpinges being played which is from the north of the area occupied by the Etruscans. It shows two seated figures who wear characteristic Etruscan wide-brimmed hats and play long salpinges, To their right, two boxers are engaged in a competition. The scene is very similar to those seen in Greek iconography although the players are not standing as the Greek salpinktes always did and they are not accompanied by a herald. The figure standing next to them holding an animal-headed staff may be the Etruscan version of such an officer. In the Etruscan context, the games were more-normally associated with funerals or other celebrations and, as far as is known, the principle of the agon was not seen in Etruscan society. Nevertheless, scenes where a salpinktes accompanies a boxing match are seen in both Greek and Graeco-Roman iconography, the similarities emphasizing the close connections between the various societies. (Figure 19 and similarly, Figure 9, above) For reference data click: IC694

A further Etruscan use of the salpinx is seen in Figure 1(b) in which the Goddess Nike blows a cup-belled salpinx. She is the Greek Goddess of victory and it is fitting that she is depicted blowing a salpinx as the role of marking victory in the games fell to the salpinktes, perhaps as a surrogate for the Goddess.

The paucity of Etruscan representations of the salpinx in Etruscan iconography points to the lack of regular use of this particular instrument in Etruria and this does not support strongly the idea that the instrument was introduced into Greece by the Etruscans. Nevertheless, the Etruscans were known for their exports of metal goods and Greek authors commented specifically on the salpinges imported from Etruria. Thus, it may well be that the Etruscans were responding to a known cultural practice in Greece and, in replacing the earlier organic bells of the salpinx, they transferred some mystical power to the instrument or, at least, led the Greeks to re-evaluate the symbolic meaning of their instrument. A number of Greek texts refer specifically to the bronze-belled salpinx and, although it is possible that this was little more than a literary device, the number of such references is suggestive of the mentions reflecting actual physical changes in their salpinx.

Such changes may have precipitated some re-evaluation of the instrument as the organological performance of the bronze-belled salpinx was so different from that of the earlier salpinges. The all-metal cup-belled salpinges which I have made are very loud, very directional in their output and are capable of sounding a very satisfying, ringing bell tone. On the contrary, the organic salpinges which I have constructed and tested are much gentler on the ear. If the Etruscans really did change the material of manufacture of the salpinx bell then this could have led to greater standardisation in its form and would certainly have led to changes in its acoustic output.

In view of the symbolism surrounding the brass in the ancient world, it is fitting that it was the salpinx which opened the Olympic Games. Its role was much more that marking the onset of an athletic completion as it also marked the beginning of the truce which was to hold in the vicinity of the games for their duration. Although no literary sources report this opening role, one Greek author, Philostratus reports of the closing of the games:

If you listen attentively to the herald, you will recognize that he always proclaims that the prize games have ceased, and that the salpinx announces the labours of Mars by calling the young men to arms. This proclamation also enjoins to remove the oil and to carry it away, since it is no longer a question of anointing oneself, but precisely of having ceased to anoint oneself.

This quotation, refers to the closing of the games and the resumption of hostilities or the labours of Mars. In writing this way, Philostratus is referring to the agency granted to the salpinx which is redolent of that seen in many societies who animise their brass. In this case, the salpinx is announcing the resumption of hostilities as it acts as an agent of the God of War, Mars.

Iconography of the Graeco-Roman cultural time and space shows the 8-foot tuba in use only within the games/agon. Such a long instrument would not be a device to run around with and, given that the bronze sheet from which all the instruments I have examined are made are of very variable gauge and frequently have a thickness in the order of 1 mm, the weight of an 8-foot tuba could well be in the region of eight to ten kilograms (approx. 18 to 22 lbs). They are thus, very-specialised instruments probably created specifically for use in the agon/games. The species is, therefore not one to function in any way as a ‘war trumpet’

Conclusions

It is clear from Graeco-Roman iconography that, during the 1^st^ to the 4^th^ centuries CE a long straight tuba existed and that the earlier Greek tradition of a salpinx context took place within the context of the agon/games, this competition taking place during the first day of the games. As the winner of this contest, the salpinktes officiated throughout the games, at some date, it became the norm to have the salpinx competition runner-up provide heralding services for the presentation of the winner’s prize.

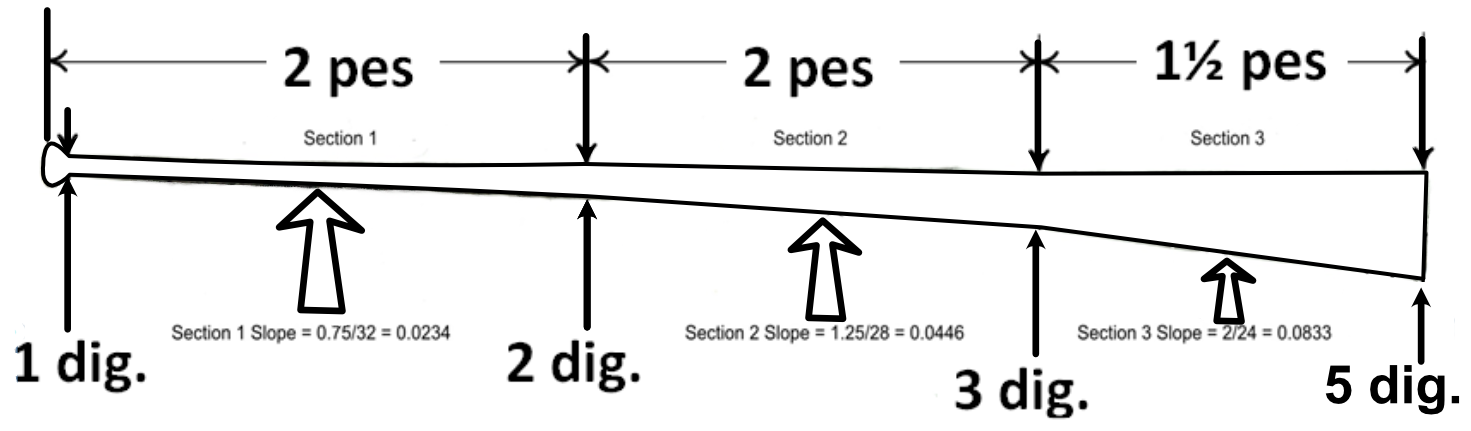

Iconographic representation of these instruments are sufficiently similar to allow one to propose a design standard with a reasonable degree of certainty. This standard appear to be one of an 8-foot (approx. 2.4 metres) long instrument, this approximating to the 8-foot C trumpets of the Renaissance/Baroque Periods. The ancient instruments’ windways are conical over much of their length with a pronounced flare at the bell end. However, the conical section has different levels of conicity (i.e. different semi-vertical angles) over the length of the instrument. Towards the instrument’s bell end, the conicity increases somewhat. A windway with this conical structure (but lacking the flare) is seen on the surviving Zsambek Tuba which is shown in Figure 19. As can be seen from the diagram, the instrument is designed using metrologically-defined elements, being 5 ½ Roman feet (pedes) overall. Its three sections are 2 and 1 ½ Roman feet long and the sections all start at a round multiple numbers of the Roman digitus. It seems not unreasonable, therefore, to propose that the long-straight tuba depicted in agonistic contexts was similarly designed metrologically rather than organologically, being made to a length of 8 Roman feet. For reference data click: SD263

The performance characteristics of these long instruments would, of course, depend very much on the type of mouthpiece used when sounding them. As the data for my study was obtained from iconographic sources, there is no indication of the type of mouthpiece employed available. However, the range of designs of the extant Roman mouthpieces provides such diversity that one is able to assign a mouthpiece to an instrument with a view to attaining a specific performance outcome. Thus, mouthpieces with a large cup diameter and large throats allow the instrument to speak readily in its lower register while those with dimensions more like a modern trumpet would enable it to speak readily in its upper register.

Modern analogues created by me and my colleagues Spike and Martin at Middlesex University confirm this view. Figure 21 shows the notes of the harmonic series which I have been able to elicit from a 3D-printed modern analogue of a Graeco-Roman 8-foot C tuba using a modern mouthpiece

As to what was actually played on these instruments, I can only reply with the politician’s answer: that’s a good question. The iconography is too sparse to provide any idea of how the long tuba evolved. Iconography such as that shown in Figure 16 does indeed show a very-long salpinx from very early on but I would suggest that this is a totally organic instrument.

A likely scenario is that the tuba replaced the salpinx some time after the fall of Greece to Rome. If this is so, the tuba in use at that time would, most likely, be based upon one of the then-current Roman forms such as that seen in Figure 21.

Such a change may well have finally broken the link to the earlier chambered instruments. In doing so, while the tuba/salpinx was still used in the agon/games (Figure 21), the removal of the links back to the ancient lore surrounding chambered instruments meant that it could be developed for its ‘musical’ qualities. For reference data click: IC689

The change in the meaning of the salpinx was not brought about by the introduction of the cone-belled or conical salpinx as classical Greek iconography shows these in use much earlier and some of these are identical in form to much later Roman tubae. (Figure 1(a)) It was more likely to be an identification of the conical salpinx with the Roman tuba and the association of Roman usage which allowed the instrument of the games/agon to be developed. Thus, a Roman form was adopted but this was incorporated into the games as an acoustic and symbolic replacement for the earlier cup-belled salpinx.

Were it to be the case that short tubae of this form were in use at this early time, any performance would need to be based upon the half a dozen or so notes that this instrument could produce. Such a performance is likely to reflect the instrument’s role as a signalling/control device.

It was likely that it was the expansion of the repertoire of events at the Graeco-Roman games which created the pressure to expand the role of the tuba/salpinx in these festivities.

Such a pressure might also have risen from mouthpiece development. The extant mouthpieces show considerable variety, some being eminently suitable for clarino-type performances15. Unfortunately, as no-one in the ancient world, saw the need to write anything about the contemporary brass or its performances, there is no way of knowing whether the underlying conceptual grasp of mouthpiece design was anything other than empirical. I believe, from studying this extant material, that it was at a level which I would describe as enlightened empirical and that there was a considerable understanding of the role of mouthpiece morphology in establishing basic operational mouthpieces.

The uniformity of throat diameters, a difficult element to control given the technology of the time, suggests that this element was well understood. While such understanding stopped short of what we might term scientific, it was probably not too different from that of the past few centuries, with the exception of the role of cup depth. Roman mouthpieces are universally more shallow than modern ones.

Back to performance and that’s up to you, the reader, to take what you will from Figure 21 and create your own score. Happy composing!

-

West 1992: p.118 ↩︎

-

The situation changed when the Graeco-Roman games appear to have transmogrified the salpinx and its competition into something of an art-music experience. ↩︎

-

Gardiner 1910:,p.139, no.3. , Turrentine 1969, p.42 ↩︎

-

Information sources are indicated using the categories utilised in http://www.hornandtrumpet.com, with IC denoting an iconographic reference, SD physical ones and SR small representations. ↩︎

-

Tuba is the Latin term applied to a straight brass instrument much like a 19^th^ century straight British coach horn, left-hand image on Figure 1, above. ↩︎

-

The concept of Complementary Duality is a very common one in both the ancient and ethnographic records and has particular significance in the world of brass instruments. It is discussed in detail in my book: Horns and Trumpets of the European Iron Age, Chapter 5. (Holmes 2022) ↩︎

-

Holmes 2022: p.2 ↩︎

-

A remarkably consistent phenomenon in both archaeological and ethnographic contexts is the view of brass instruments as providing a space (a Chamber) within which powerful spirits might reside or from which creation or re-creational acts may emerge. It is discussed below and in The Horn and Trumpet in Iron-Age Europe. ↩︎

-

While the term ’lituus’ is used to describe their J-shaped instrument, we do not know what the Etruscans called this and today we borrow the Latin term as the Romans possessed devices of a similar form to which they applied this terminology. ↩︎

-

Holmes 2022: Chapter 7 ↩︎

-

Holmes 2008: pp.241-260 ↩︎

-

For the tomb, see Steingräber 1986, no. 162. Jannot (2009, 83) claims that the Etruscans probably never saw real lotus flowers, but rather picked up on the icon from imported art; he reports that botantists claim that the lotus did not come to Italy until the 15^th^ century. (Footnote from Lisa Pieraccini) ↩︎

-

Steingräber 1986, no. 81 (Footnote from Lisa Pieraccini) ↩︎

-

For the fifth century BCE bronze mirror from Palestrina (Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia, Inv. 12973), see Helbig and Speire 1963–72, 833. (Footnote from Lisa Pieraccini) ↩︎

-

The clarino player during the Baroque Period played the upper (higher) part which was generally the most demanding. ↩︎